justice hema :-The evidence implies that well-known, well-reputed males in the industry “have shocked certain women in cinema by sexual harassment and physical advances made by them,” according to the Justice Hema Committee report.

Thiruvananthapuram: The shocking revelations of the Justice Hema Committee report on harassment faced by women in the Malayalam cinema industry have evoked strong reactions across society, demanding stringent actions to ensure a safe working atmosphe…

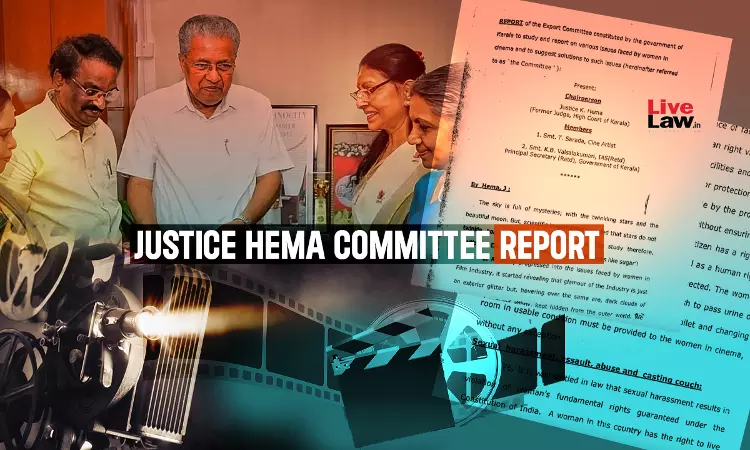

NEW DELHI: The Kerala government on Monday released Justice K.

Hema Committee report which revealed troubling aspects of Malayalam film industry including casting couch and sexual exploitation faced by women.

According to the Committee, the evidence suggests that well-known, well-reputed men in the industry “have shocked certain women in cinema by sexual harassment, and physical advances made towards them.”

an offer for a role in cinema first approaches the woman/gir ..woman/girl or if it is the other way and a woman -approaches ..

justice hema The informal nature of work — which includes a lack of legal contracts or grievance redressal mechanism, and an inbuilt culture that emboldens powerful men who control the fate of many within the industry — has led to rampant sexual harassment across the profession.

Widespread Exploitation and Gender Disparities

The report exposes a troubling culture of sexual exploitation and disregard for women’s rights within the industry. It highlights the persistence of practices like the casting couch, where women are often pressured into offering sexual favors to secure roles or avoid being blacklisted.

The three-member committee, consisting of retired High Court Justice K. Hema, former actress Sharada, and retired IAS officer K.B. Valsala Kumari was founded in response to a demand by the Women in Cinema Collective.

This demand followed the abduction and sexual assault of a leading female actor in February 2017—a case that remains in trial, with prominent actor Dileep listed as the eighth accused.

“In the course of the study, we understood that the Malayalam film industry is under the control of certain producers, directors, and actors—all male. They control the whole Malayalam film industry and they dominate other persons working in cinema,” the report states.

The committee identified at least 17 types of exploitation faced by women working in 30 distinct industry groups. These include sexual demands made on women seeking employment in the sector, sexual harassment, and different forms of abuse and assault. The survey also mentioned transportation and housing challenges, which exacerbate the hazardous environment for women.

The report also highlighted the violation of women’s rights through the failure to provide basic amenities, such as toilets and changing rooms on film sets. Women working in the industry often face a lack of safety and security, both in their accommodation and during transportation.

The assessment also stated that the establishment of an ICC, as required under the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act of 2013, would most likely be unsuccessful.

justice hema Many women testified that they could also face threats to life, not only to themselves but also to their close family members.

The report explains that “there is a culture of silence that shrouds Malayalam movie (industry), which is partly a fear psychosis engendered by the working of the power nexus that controls” the industry.

Witnesses told the Committee that nobody would speak out because the powerful men “feel if a woman is a ‘problem maker,’ then nobody will call her again.” Many people suffer silently due to this, a witness said.

The report also notes that the industry seems to have an “unwritten understanding” that those who complain against negative behaviour and fight for their rights “need not be called again for a movie.”

Thus, they were being silenced, says the report.

The silence is also structural.

The Committee says that based on their interaction with men and women from both older and younger generations of the industry, they found that ever since the industry originated, women have faced such issues. However, there has been no grievance redressal mechanism.

On the rare occasion that a woman does complain to a producer about an actor or director, “the producer will not avoid him from his cinema” if this actor or director “has good market value.” This is mostly because of “financial reasons,” the report says.

A witness explained to the Committee that if a woman tells her colleagues about being harassed by the director, “the normal reaction of the crowd around her will be to silence her and they will ask her to compromise and adjust; let the cinema run.”

On the contrary, the witness said, “male superstars, directors or producers or anyone in such power position can do anything.”

”He only stated that there is nothing to be scared of and that he will do only as she consents to,” said the report.

After three months of preparation, the director informed her that there would be nudity and a kissing scene. “She was forced to do a kissing scene and expose the back part of her body.”

The female actor walked out of the movie without even claiming her three months of remuneration.

She also sent a message to the director stating that she had lost faith in him. “But he insisted that unless she comes to Kochi personally he will not delete the intimate scenes.”

When she realised she was being blackmailed, she informed the producer. “Had there been a written contract such a crisis could have been avoided,” the report says, stressing on the importance of a formal redressal mechanism.

Until the formation of the WCC, the fear ensured that even among women, accounts of abuse were kept a secret. A WhatsApp group created by the WCC, which offered confidentiality, became a space for women to chat openly and state their concerns.

The women told the committee that with the WCC, they found a safe forum to discuss accounts of sexual harassment which they were not able to “disclose even to family members.” Their families were already reluctant to allow them to work in an industry where women had a “bad name.”

On and off-screen expectations

According to several women who spoke to the committee, a majority of men who work in the industry think that the women who are willing to act in intimate scenes would also be willing to do the same off-set. So men in the industry make open demands for sex with little hesitation or embarrassment.

Even if women express their resentment and objection to such demands, the report says, these men would continue to ask for sex, offering them “more chances” in films. The committee was informed that some women, especially newcomers, fall prey to such offers and are sexually exploited.

The committee also received access to audio, video clips, screenshots of WhatsApp messages, and other digital evidence that showed how certain people in the industry persuaded women to make themselves available for sex.

Cinema has been a passion, a long-awaited dream for many of these women. But this exploitation has made them reject many offers, the report says.

A few men claimed to the committee that women face these experiences only when they fall for “fake advertisements.”

However, according to the article, the committee examined the data and confirmed that women endure sexual harassment from “very well-known people in the film industry, who were named before the committee.”

Though all particular examples of such exploitation have been censored, the study does reference one woman’s experience on a film set shortly after such an incident occurred.

“On the following day (meaning the day after she was harassed), she had to work with the same man as husband and wife, hugging each other. That was dreadful. Because of what had happened to her, her wrath and hatred were reflected on her face during the shooting. Seventeen retakes were required for a single shot. The director criticised.

Men and ‘Not all men’

The Hema Committee report also details that the evidence suggests that not all men are responsible for “the bad reputation” of the industry, and that there were several “highly respectable men” who ensured a safe environment.

A cinematographer and a director were specifically mentioned, but their names were not given in the redacted report.

But several men had “tried to impress upon the committee that sexual harassment exists not only in cinema but in other fields as well. Therefore, sexual harassment in cinema may not be blown out of proposition,” says the report.

However, according to members of the Committee, the women who spoke to them brought to their notice that “there is a striking difference between sexual harassment in cinema and other fields.”

‘Casting couch’ and lack of safe spaces

justice hema In no other industry are women forced to take their parents to their workplace, the report says.

“A teacher, clerk, engineer, or doctor will not have to take their parents when they go to work to their office.”

This knocking is neither “polite or decent,” but a repeated banging of the door. “On many occasions, they felt that the door would collapse and men would make an entry into the room by force.”

The Committee stated that there is direct evidence from witnesses.

The Kerala Government constituted the Hema Committee report in 2017 in response to the Women in Cinema Collective’s demand to investigate the problems that women experience in the industry.

On July 6, the State Information Commission (SIC) passed an order directing the Kerala government to issue the committee report to RTI applicants before July 2, after redacting information that could identify individuals mentioned in the report, as prohibited under the Right to Information (RTI) Act.

Read Also:-https://indydeafnews.com/saif-ali-khan/

3 thoughts on “justice hema committee report malayalam…”